Update: Added new NCTE online book rationale database link in the list below.

Update 8/26: I have also added the Brooklyn Public Library's Books Unbanned resource page.

What do you do when a parent calls to complain about a book your students are avidly discussing? Or when your principal tells you that teachers should never discuss politics with students (after you provided them with the opportunity to read a book for young adults that was on the New York Times bestseller list and the movie had just been released, so students actually wanted to read it)? Or your state passes legislation that would cost you your teaching license for doing what you know is pedagogically correct?

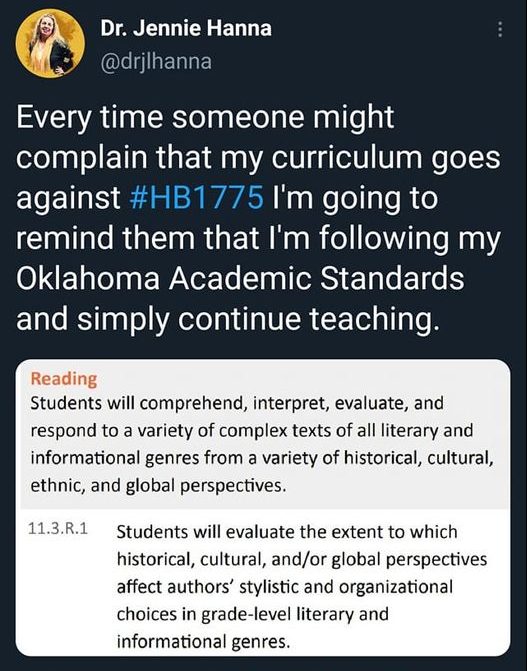

What do you do when your district calls you out of class for giving students a QR code that links to a public library's "books unbanned" resource page and covering a cabinet of books in your classroom with paper and writing the words “Books the state doesn’t want you to read” on it -- a reference to the HB 1775 bill the Oklahoma governor recently signed into law, which she also referred to as "bigoted legislation." (To be clear, bigoted means "blindly devoted to some creed, opinion, or practice" or "having or showing an attitude of hatred or intolerance toward the members of a particular group (such as a racial or ethnic group)." The local newspaper article states the bill "prohibits public school teachers in the state from teaching anything that makes a student “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress” because of their race or sex." So far, this legislation has resulted in two districts having their accreditation penalized, one for a training that a teacher claimed shamed white people and the other for a voluntary "cross the line" student activity designed to build empathy among diverse groups by helping them see their similarities and differences in an effort to reduce bullying.

The video above by MSNBC, "Too Scared To Teach: New Restrictions In Classrooms Force Teachers To Self-Censor," which features an interview with Jen Given, 10th grade history teacher at Hollis Brookline High School, discusses the ethical dilemma we're facing in our classroom, which will create what H. Richard Milner IV in an article on the ASCD website from November 2017 called the null curriculum.

“The null curriculum refers to what students do not have the opportunity to learn. In this case, students are learning something based on the absence of certain experiences, interactions, and discourses in the classroom. For example, if students are not taught and expected to question, critically examine, and call out sexist language in books, they are learning something—that it may not be essential for them to engage in this work of critique and exposure. In other words, what is absent or not included in the curriculum can actually be immensely present in what students are learning,” Milner wrote.

Jen talks about speaking publicly about what we are facing as teachers and what we are ethically bound to do in service to our students. But what can you do when you're still in your classroom?

Back in 2018, I recognized that my students did not have access in school to recent young adult works by Black authors in America. They weren't in our library and not on our reading lists. But when I brought the books into my classroom library, students expressed interest because the movie version of The Hate U Give had just been released. In previous years, I started witnessing and recognizing my minoritized students struggling with issues my white students never experienced and I wanted to help them empathize with their peers. I wanted the students in power to help me create a safe school environment for all of them.

I knew that I worked in a conservative community, but also that my students had questions and most of them were wanting answers. So I created literature circles and asked each student through a Google Survey which book they wanted to read out of four I had selected: Tulsa Burning by Anna Meyers and Dreamland Burning by Jennifer Latham (both white authors), The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas and All-American Boys by Jason Reynolds (both Black authors). For the record, Reynold’s book was also co-authored by Brendan Kiely, a white author.

Students choose which book they wanted to read and which group of peers they wanted to read with. I did have a few students switch books. Only one student disliked all four books, but loved The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, which I gave her the option to read in lieu of the other books. She ended up up creating a presentation on why that book ought to be taught in high school as her final project for the unit. (She had the option to argue that the book should not be taught in high school also. In either case, she needed to include her reasons why she chose that side and include evidence from both the book and outside resources.)

While reading the books, students engaged in recording their Thoughts, Questions, and Epiphanies (TQEs) and creating questions they thought would be important to discuss as a whole group. After we reviewed our goals for the discussion, which included gaining a better understanding of the author’s purpose and differing opinions, group leaders read one of two questions they’d submitted and then discussed their understandings, which me facilitating the process. We did have a couple of moments where students struggled to understand a different perspective, but they worked their way through in class.

I tell you all of this because even in 2018, I got called into the office and spent an hour defending my teaching practice because a parent called to complain that I was “teaching police brutality.” I knew this was going to happen because one group of students reported to me that a couple of students thought I was a terrible teacher for making them listen to other people’s ideas. So I wrote up a description of the unit I was teaching, and choices students made, how they were handling the discussion, and my role in facilitating it. My ability to explain my pedagogically sound rationale for the unit diffused the situation and I left the meeting unscathed. That might not be true today though under new legislation. The courts will have to decide. Until then, what can you do?

My advice is to start planning now for this to happen to you — assuming it hasn’t already.

As teachers, we walk a fine line between appeasing parents and administrators and actually educating and advocating for our students. On one hand, we can’t do our work without our jobs (which are now being threatened), and on the other hand, we can’t do our jobs because some people only want one side being taught (while simultaneously accusing the other side of indoctrinating students).

“Censorship leaves students with an inadequate and distorted picture of the ideals, values, and problems of their culture,” according to The Students’ Right to Read published by the National Council of Teachers of English.

Censorship, combined with the already existent null curriculum can leave students with a very incomplete, one-sided understanding of our history and culture. As an English teacher, it is my duty to not only help all of my students see themselves in the literature they read, but also experience literature as a window into other worlds. This is especially important for understanding and connecting with people from various cultural and linguistic backgrounds that one might meet through work, in continuing education, in church, and in other areas of our lives. I know that my life has been enriched by relationships I’ve developed with people from backgrounds unlike my own — whether they are much younger, from a different country, speak multiple languages, or are a different gender — and I want my students to be able to communicate and collaborate with the people they encounter in their lives.

I also know that this can seem like an impossible goal in today’s political climate. However, I have a list of resources I curated for a symposium I spoke at with the University of Oklahoma in 2021. While the situation has worsened, I think the methods of responding proactively and advocating for your students remain the same:

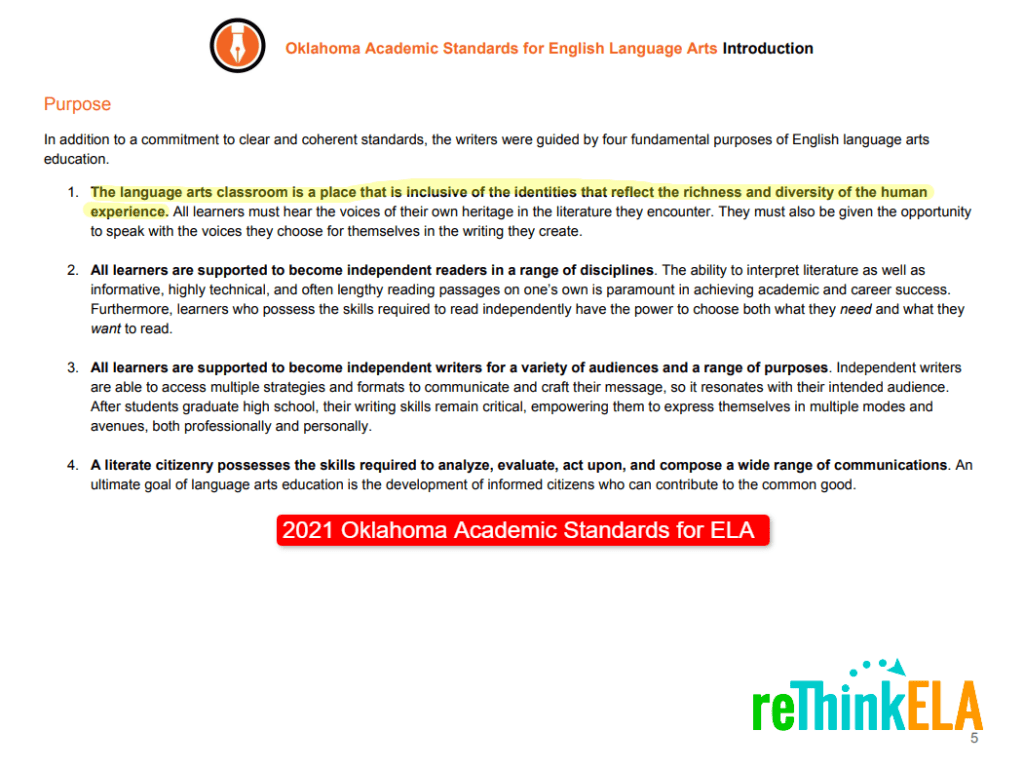

Finally, remember this purpose statement from the introduction to the Oklahoma Academic Standards:

If you have any additional insights into how to meet the educational needs of your students and honor their right to read in an increasingly divisive climate, please reply in the collaboration area below.

Get more resources to help you manage censorship in your ELA classroom

Just enter your first name and email address below. I recommend using a personal email address to ensure you receive our emails.